Point of Origin Episode 18

Culinary Commodities

On our first stop today we travel to India to learn about what may be considered the world’s only seafaring fruit, the coconut! We’ll explore its nomadic origins and how its growing global popularity has impacted small farmers in the Global South.

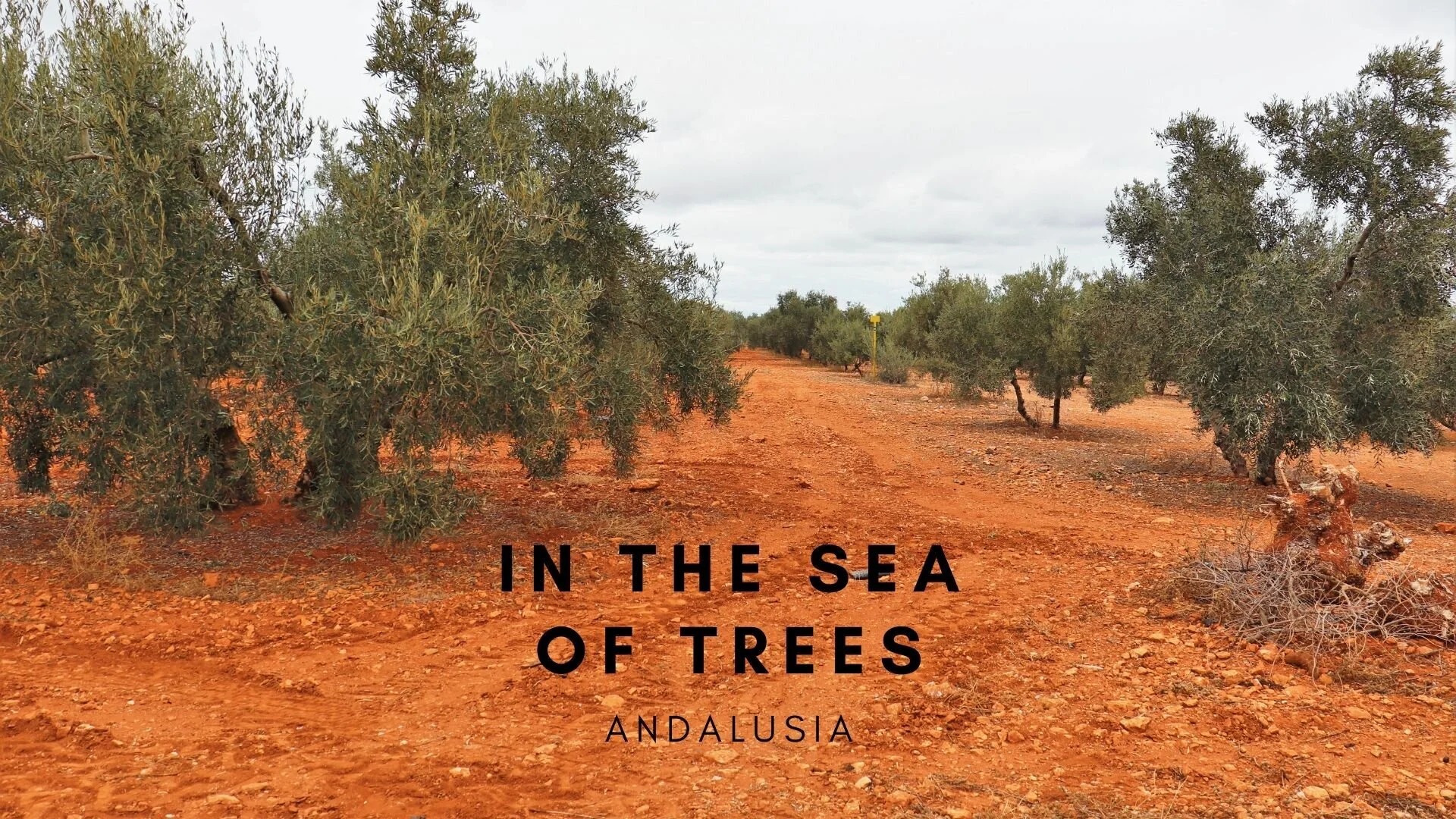

Next we meet Whetstone Co-Founder, Melissa Shi, in Andalusia, where we are re-introduced to another familiar fruit that is used to produce one of worlds’ most ancient cooking oils. Olives, of course.

As we follow these familiar culinary commodities on their journey from their place of origin to our kitchens and plates around the world, we learn about their respective traditions and how market demand is shaping their future.

A note to consider: We made this episode in the beginning of year, but find these stories to be even more relevant in today’s global health crisis. As workers worldwide risk their lives to feed their families and the world, more than ever, we are forced to reconcile the interconnectivity of our consumer choices.

Available on Apple Podcast, Spotify, & iHeartRadio

The world’s only seafaring fruit?

With Organic Farmer Simrit Malhi

“As a seafaring fruit, the coconut has been floating on the seas, sprouting on whatever tropical coast it lands on for millennia. It is the indigenous food of countless countries, from Asia and Africa to South America and the Caribbean - belonging equally, everywhere. It is an essential part of the ubiquitous trinity of tropical coastal food – coconut, fish and rice.”

On today’s episode, we explore why farmers in Simrit’s region of Tamil Nadu are considering the coconut as their next crop, and what growing global demands have meant for communities in South Asia.

A growing, global appetite for coconut

According to Orbis Research, in terms of revenue, the global market size will reach $ 1.7 billion by 2025, from $ 873.8 million in 2019. Over the last two decades, demand for coconuts – for reasons culinary and cosmetic — has surged. Coconut byproducts like juices, oils, creams have become cornerstones of the “wellness economy.” But what does growing demand mean for farmers?

Our first guest, organic farmer and permaculturalist, Simrit Malhi, discusses the coconut’s role as the tree of life, and how for many coastal communities and island cultures, just four or five trees are enough to sustain a family. But these days, coconuts have become more expensive than food, and are now being sold for other goods.

“…. now those four coconuts that a family has on an Island, they would rather sell it. And get money and buy those clothes and fuel from somewhere else instead of using the coconut they have….”

Simrit notes that today, similar to practices used in palm oil production, forest-clearing in order to plant coconut farms has become a new norm. In Indonesia, we can see how they became the world’s largest exporter, steadily increasing production to meet a growing global demand.

Spain is home to about 300 million olive trees, which produce half of the world’s annual olive oil supply. In today’s olive oil world, most large bottlers are buying oil, not actually making it themselves. They buy bulk olive oil from across the Mediterranean, then blend and bottle it. A lot of oil found in the market will read “Packed in Italy”, but the oils are from Italy, Greece, Spain, Tunisia, Morocco and beyond, with a very low level of traceability and transparency.

In today’s episode, we learn about the challenges that a highly commoditized market brings to small and regional farmers, and what the future looks like for these heritage crops.

The Harvest at Oleoestepa Co-op

Over 5,500 farmers grow and produce olive oil cooperatively at Oleoestepa. The co-op is vertically integrated, from tree to export. They collaborate with farmers to protect the quality of fruit through organic farming, and carefully harvesting, milling, storing, and bottling their single origin oil oil. While hand picking is still practiced among smaller family farms, many commercial producers in Spain utilize technology that gets olives to the mill more quickly.

Harvest time

Oleoestepa incentivizes its farmers to pick early. Even though greener olives produce less quantity, they produce a higher quality oil. Farmers working with handheld tools and large machines work quickly harvest olives from the trees. Once picked, various processes like fermentation and oxidation are naturally and slowly beginning to in the fruit. These can cause flaws in the final product, so it’s a race against the clock to get these freshly picked olives milled as quickly as possible. Most olives picked are milled into oil within a matter of hours.

The Mill

During harvest season in November and December, each farmer brings their daily harvests to one of Oleoestepa’s 17 regional mills. Our farmer inputs information to signify details like variety, time of harvest, plots harvested. Each mill’s process is highly technical and data-driven, providing a deep level of traceability that is uncommon for many food products and especially olive oil. Later scenes shown here are examples from nearby mills, which illustrate the final product. Oleoestepa uses all closed processes in order to manage oxidation.

How to Buy and Store Olive Oil

With Kyle Davis // Oleoestepa Co-op

What does olive oil expert Kyle Davis recommend? Key factors to consider are date of production, source, and looking for bottles that protect the olive oil from light.

The Olives of Andalusia

There are over 200 varieties of olives grow in Spain.

Here are some of the cultivars we meet in this episode.

A handful of olives from the Olivoteca or Olive Museum in Seville showcases a vast biodiversity in olives – there are thousands of cultivars grown worldwide! The unique characteristics of each variety, including hardiness, disease, pest or drought resistance, can provide a key to solving the problems that arise from mass, intensive cultivation.

Preserving biodiversity is also preserving culture. Here are some favorite olives and oils and notes on their varying flavor profiles.

Hojiblanca Olives

This Spanish cultivar is named for the distinct pale coloring of the undersides of its leaves, translating to “white leaf.” Hojiblanca olives are firm, with low oil yield, but deliver high quality, polyphenol rich oil.

Arbequina Olives

Arbequina are highly aromatic and small, but deliver some of the highest yields. They’re sometimes used as table olives, and generally mild in flavor.

Picual Olives

Robust, high intensity flavor, the Piqual yields large amounts of oil - because of it’s vigor, hardiness and adaptability, this cultivar is the world’s most prolific olive, accounting for half of Spain’s olive trees.

Gordal Sevillana Olives

Gordal Sevillana are very large, but have an extremely low yield of oil, thus they are mostly suitable as table olives.

Manzanilla Sevillana

This is one of the main table-olive varieties in Spain. It is mainly grown in the province of Seville where it is also used to produce oils known for their medium fruitiness and hint of spiciness and bitterness.

Zarza

This olive is unique to Spain and considered a novelty variety as it’s culinary uses are limited. This cultivars fruit is uniquely ‘star’ shaped towards the end, with a distinct wrinkly appearance.

Tasting Olive Oil

With Oleologist Alfonso Fernandez

Is there an intensity of aroma ?

Look for “fruitiness” and how intense is it?

This can be thought of in terms of robust, medium, or low

What type of aroma are we getting out of the olive oil ?

For extra virgin olive oil, the aroma should remind us that it is alive and fresh like green grass. If it’s smelling musty, fermented, or rancid, these are not good properties

Put the olive oil in your mouth and sip!

Salivate properly to absorb the full flavor. Take a little sip — inhale sharply through your nose to bring in oxygen, and remember to keep the olive oil in your mouth for 30 - 45 seconds. Swallow and enjoy.

And what is Alfonso’s favorite way to eat olive oil? Cooking a sunnyside up egg!

Meet this Episode’s Guests

Simrit Malhi // Roundstone Farms

Simrit Malhi is an organic farmer from Kodaikanal in Tamil Nadu. She is the main permaculture designer at her family farm in Kodai called Roundstone Farms. The farm is completely organic, as biodynamic, planned according to permaculture principles with swales, waterways, ponds, grey waste water systems, a bio gas plant and a fully natural home built using ancient Tamil methods with stone and lime mortar. The farm produces many fruits like Avocados, Peaches, Guava, Starfruit, Passionfruit, Oranges, Pepper, Coffee. Simrit has been actively involved in farming from a very early age and her interest in farming and farm produce has only grown over the years.

Kyle Davis // Oleoestepa Cooperative

Kyle Davis, is responsible for the export of Oleoestepa in the Americas. He has worked with the cooperative in Andalusia in order to distribute the high quality oil that comes from the area in Spain.

More than 5,500 farmers families in Estepa, Andalusia - Spain, makes the magic happens with effort and hard work, generation after generation. In a very close cooperation with their agronomists and the mills the olives are harvested in ideal moment.

Oleoestepa produces extra virgin oils obtained primarily from Arbequina, Hojiblanca and Picual olives.

Alfonso Fernandez

Alfonso Fernandez is an olive oil and wine taster in Spain. For years, Alfonso J Fernandez has been working in the olive oil business. His family has been involved in olive oil production and cultivation for five generations. Living in Andalucia, the largest production area worldwide, Alfonso travels worldwide to educate the public from chefs to journalists about olive oil from Spain.

Ana Sánchez Lago // Fundacion Juan Ramón Guillén

She is the General Coordinator for the Fundacion Juan Ramón Guillén, with the mission of preserving olive oil culture. The Foundacion as part of Hacienda Guzmán hosts an olive tree museum with more than 150 varieties from 13 countries around the world. This museum allows for study of properties and particularities of trees from diverse places like Portugal, Greece, Syria or Albania. It is a unique place where visitors can perceive the diversity of the world of the olive grove.

The olive oil history of Hacienda Guzmán Mill dates back more than five centuries, when Hernando Colón, the son of Christopher Columbus, exported the olive oil produced at the Hacienda to the Americas. Between the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries, each of the three towers of the hacienda housed a beam mill, making it one of the largest olive oil factories in the world.

It’s very important for us to discuss this history, namely the unmeasurable repercussions and role that the original founders played in the colonization of the Americas, to it’s native, indigenous and enslaved peoples, and how these practices benefited them and brought prosperity to the region. While the ownership of the mill has long since changed, this history is important to remember and acknowledge

Sources:

https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20190919005726/en/World-Coconuts-Market-Analysis-Forecast-Size-Trends

https://www.indexmundi.com/commodities/?commodity=coconut-oil&months=240