Handing Down Hawker

A street hawker at Trengganu Street in Chinatown, 1971.

Madam Lam started the Cho Kee Noodle business in the mid-1960s, parking her modest pushcart each day under a tree to shelter from the relentless Singapore sun. She was selling her well-known wonton mee, a noodle dish served with plump wontons, char siu pork slices, leafy green vegetables, pickled chilies and a side of broth. Her days were long, lasting 18 hours, six of which were spent preparing the components of the dish in the morning for the lunch, evening and supper foot traffic. The recipe was a nod to her Cantonese heritage, and her simple cart was part of the hawker culture that had existed in Singapore since the mid-1800s.

Madame Cho photographed visiting government ministers in the 1970’s.

Hawkers are itinerant street vendors selling affordable food from baskets, carts or stalls in populated areas within the city. Specializing in a particular dish, hawker stalls can still be found across South East Asia in countries like Thailand, Malaysia, Hong Kong and Singapore.

Singapore’s rapid evolution from a kampong (rural village) to a thriving metropolis is reflected in the street food culture. Over the decades, these cultural backgrounds have fused together in the creation of new Singaporean dishes like roti prata, combining paratha flatbread from India with a Malaysian-style curry sauce, and katong laksa, a local adaptation of the spicy coconut noodle soup made by Peranakan people (an ethnic group of Southern Chinese that had migrated to the Malaysian archipelago). Singapore’s unofficial national dish is chicken rice, originally created by migrants from Hainan. The chicken is poached and served on savory rice boiled with a side of sliced cucumber and a drizzle of dark soy sauce and garlic chilli paste.

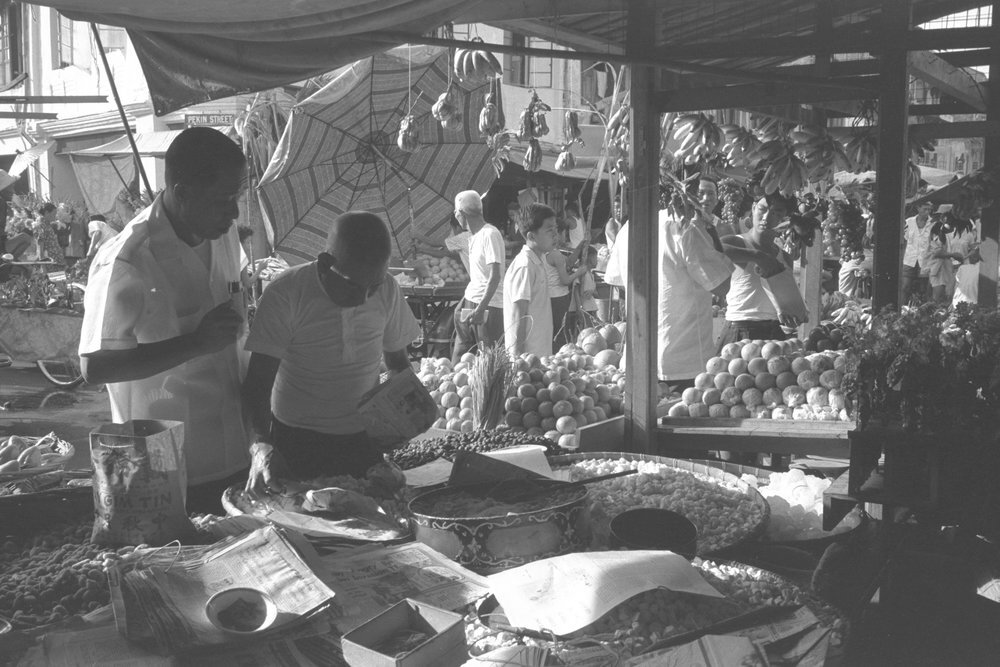

Hawker sellers at a day market in Singapore’s Chinatown district, 1962.

A night market in the same area, 1965. Both photographs courtesy of National Archives of Singapore.

When Singapore was freed from Malaysian rule in 1965, the Singaporean government realized the challenges of hygiene, waste issues and traffic obstruction that blighted street food culture. The government set up designated open-air food complexes known as hawker centers. Imagine a bustling center, stalls lit up with colorful signboards and photographs of the dishes, aromas of different spices wafting through the warm air. Locals and tourists alike lineup for the mainly Chinese, Malay and Indian specialties, on top of other regional cuisines, for just a few dollars a plate.

In these centers, the multicultural Singaporean society could dine affordably in a sanitized environment. Regulated and licensed by the government, these centers were modern, situated next to public housing, with a multitude of small stalls, clean running water, proper sanitation and modern facilities. By moving the hawkers from the street to the centers, highlighting the food and bringing in the community, Singapore created a unique hawker culture that the government describes as: “The belly of the nation”.

Brightly lit signboards illuminate diners meals at the hawker stalls in Chinatown Food Centre. Each stall displays vibrate photographs of their specialty dish.

For Madam Lam, her hawker stall is a true family business. She and her family left the pushcart behind in 1973, relocating to the same hawker center where the business is today on the Old Airport Road. Her son, Kong, starting work at the stall at just 10 years old, running up and down the public housing block to deliver the residents’ noodle orders. Madam Lam continued running the stall with her father until she handed over the reins to Kong in the ’90s. He, in turn, looks to his daughter, Ai Min, for support.

Fish head noodles, a favorite dish of Singaporeans.

Ai Min remembers growing up in the hawker center, and when her parents and grandmother were busy cooking, a lady at a nearby stall would take her brother, Jonathan, to the roadside bus stop nearby so he could go to kindergarten.

On weekends and school holidays, Ai Min and Jonathan would be assigned the wonton recipe “as it was the easiest thing to make and it wouldn’t get spoiled, given the adults can just squeeze it back into shape,” she remembers.

When the N1H1 flu hit in 2009, there was a nationwide shortage of eggs. Noodle manufacturers were omitting them from the recipe, affecting the quality and taste of noodles.

Ai Min’s mother, Soh Siew Choo, decided that she would start making fresh noodles, beginning with a small batch noodle machine that took almost a year of trial and error to get the recipe she wanted. Choo then spent another year in what Ai Min calls “Noodle R&D” to perfect it. After seeing demand from the younger customers and health-conscious diners, she started experimenting with making her own colorful vegetable varieties like spinach, beetroot and wholemeal noodles to differentiate from neighboring stalls.

Outside the Cho Kee Noodle stall, a sign advertising their homemade vegetable noodle selections reads,“All noodles sold are solely made by Cho Kee with high-quality flour, fresh eggs and are low in sodium & additives. All Veggies Noodles contain real vegetables.”

A Cho Kee Noodle dish: Wonton Mee noodles with bok choy, wonton dumplings, char siu pork shavings and a broth side.

“My parents have always been so motivated to move forward, never afraid of hard work,” Ai Min says. “It would have been so much easier just to get noodles from a supplier.”

The Cho Family attempted to grow the business by branching out into new outlets but found that it was hard to maintain the same quality dishes or hire good people to stay. So in 2017, the family made a decision to consolidate into just one manageable stall with a central kitchen nearby.

Cho Kum Kong awaits customers inside Cho Kee Noodle stall in the Old Airport Road hawker center.

Ai Min swapped her well-paid banking job for the steaming hawker kitchen, along with her brother Jonathan, despite their parent's discouragement and concern they would be wasting their education. But Ai Min believes, “For every generation, there has been a different contribution. First, my grandmother came out with the dish, then my mother and father's most significant contribution was to produce our own noodles, which is really the essence of the bowl. For my generation, how will I add value? It’s about survival.”

Even now, a hawker’s life can be a thankless vocation: long hours laboring in partially outdoor conditions, comparatively high costs of rent, with little financial reward at the end of the day.

But it was a passion for the business that drove Ai Min and Jonathan back. Ai Min adds:

“People ask, ‘You can still eat there every day? Don’t you get sick of the taste or the smell?’ But I don’t—it’s a true love! My brother and I can eat wonton noodles twice every day forever and never get sick of it.”

Ai Min, dedicated to seeing her family business thrive, prepares a dish at Cho Kee Noodle.

Multigenerational hawker stalls are becoming rare these days due to difficult working situations in a country regularly cited as the most expensive in the world. It’s a dying art and there’s no one to replace the original hawkers. With a median age of 59, the aging hawkers tend to retire or leave the industry, and there are few opportunities for ownership succession. In some ways it’s understandable younger generation don’t desire a lifetime cooped up in a tiny, hot kitchen, working 14-hour days for only mediocre wages. But this reality puts traditional recipes and methods at risk of being lost. The government needs the industry to continue not just to provide local residents with affordable dining options, but to ensure Singapore retains its national food identity that has evolved from a multiethnic society.

The Singaporean Government has placed a nomination to include hawker culture in the UNESCO Representative List of the Intangible Heritage of Humanity. Previous successful culinary nominations have included the art of Neapolitan pizzaiolo and kimjang, the making and sharing of kimchi in the Republic of Korea. Singapore’s neighboring countries have reacted negatively to the bid believing that hawker centers are not unique to Singapore as they are found in many Southeast Asian nations.

But this bid allows for the celebration of traditions, practices and events that represent a community, a culturally amalgamated region and families like the Cho’s.

Ai Min and her father Cho Kum Kong stand proudly outside Cho Kee Noodles.

Kong thinks the bid has made a marked improvement, saying that he feels “a light has been shone on the hawkers,” and there’s been recognition for the contributions they’ve given to society.

When asked about how this recognition is different from the Michelin Guide, introduced in Singapore in 2016, he says:

“The Michelin Guide is purely just about the food, but the UNESCO bid is about the relationship with the hawker, the community dining spaces and the culture.”

Cho Kum Kong serving Cho Noodles to Singapore’s current Prime Minister, Lee Hsien Loong, at a food fair.

Kong touches on the future of the hawker centers, highlighting his original concern that they may all be demolished or turned into Western-influenced food courts. But he’s optimistic, “People will come to the hawker center, not just to go for the Western-style or the Japanese stalls, but to eat our local food, like what I am selling. It means that my family will continue to run this stall for generations to come.”